Exciting fossil find in Grasslands National Park surprises palaeontologists

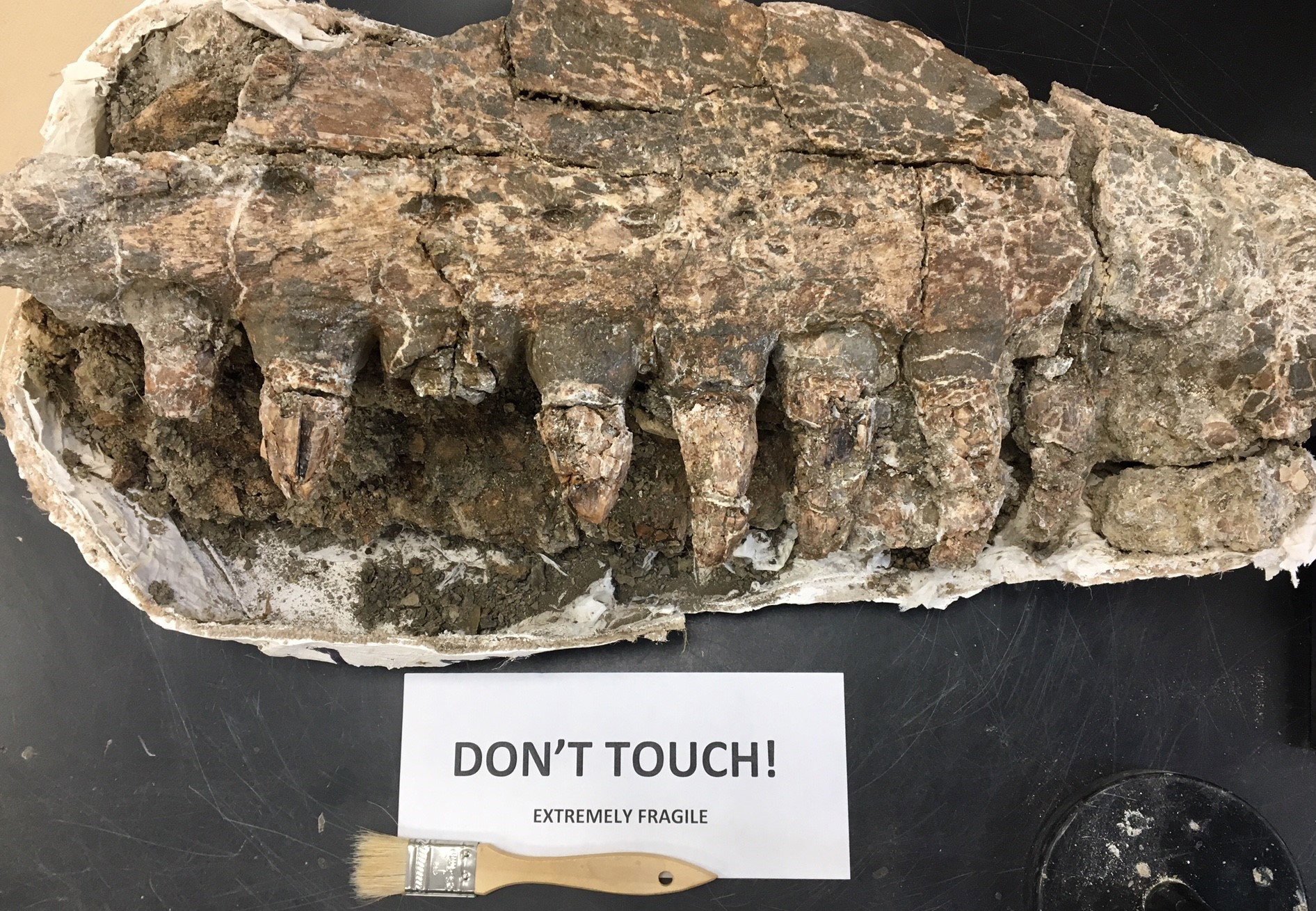

Posted on 16 December 2021 by Ryan Dahlman A display of the pieces of a Prognathodon fossil found on a site in the Grasslands National Park.

Photo courtesy of Royal Saskatchewan Museum

A display of the pieces of a Prognathodon fossil found on a site in the Grasslands National Park.

Photo courtesy of Royal Saskatchewan Museum

Staff from the Royal Saskatchewan Museum (RSM) got a pleasant surprise when they made a brief trip this fall to a fossil site in Grasslands National Park.

Small fragments of the skull of a Prognathodon, a prehistoric marine reptile in the extinct mosasaur family, were found on this site during previous field trips several years ago.

This time a large skull was uncovered that measured approximately 130 centimetres, which is noticeably longer than the 80 to 90 centimetres of three other specimens collected in Alberta.

Dr. Emily Bamforth, a RSM palaeontologist at the T. rex Discovery Centre in Eastend, said the size of the skull makes this a significant fossil find.

“This particular fossil is the first occurrence of this species in Saskatchewan,” she said. “So it’s important for that reason, but it’s also important because it’s so big. This is the biggest mosasaur we’ve ever found in the province. So it’s very exciting for that reason too.”

Uncovering the Prognathodon skull during the field trip in September was a significant step in clarifying the importance of this fossil. Its original discovery in the West Block of Grasslands National Park took place nearly a decade ago.

A previous owner of the land found fossils on this site. A RSM palaeontologist visited the site in November 2012 and collected some Prognathodon skull fragments. Other fossil material was collected on the surface in 2013.

“They basically collected what they found on the surface, which were kind of the tips of the upper and lower jaws as well as some of the vertebrae, but at that time they weren’t able to do any excavation,” she said. “So it actually wasn’t until this year that we applied for a collection permit to go back to the site. We didn’t know if there was more material still in the ground. We didn’t know if what was on the surface was all there was. So we really had no idea what to expect when we went back there.”

She added that there was no intention to already go back to the site in 2021. The opportunity came up when some planned fieldwork at another location in the province could not take place.

“And so as a plan B we decided that we would go this site in the West Block of Grasslands instead, just to check it out,” she said. “We had no idea what we were going to find and it was just going to be kind of an afternoon out there. It turned into a two-day frenzy to get what we could out of the ground before the winter set in. This was the end of September. So it was late in the season.”

According to Bamforth this fossil site is very interesting for a couple of reasons. Their first observation upon arrival was that there were bits and pieces of fossil on the surface.

“There was some bone on the surface that had just basically been sieved out of the ground,” she recalled. “It’s kind of a muddy shale, and when it gets wet it expands and as it expands the fossil gets pushed to the surface. … We figured out where we should start poking around and within 20 minutes of being there, we discovered fossil that was just centimetres under the surface. It was very, very close to the surface. We were really just using brushes and a bricklayer’s trowel. That was all we needed. We didn’t need any shovels or pick axes. It was all very close to the surface.”

Their excitement increased as they started to uncover the details of the fossil materials in the area where they were working.

“We found the upper jaws, both of them, and then we found parts of the back of the lower jaw and parts of the top of the skull, as well as more vertebrae,” she said. “It was kind of exciting for me. I was the one that found the upper jaws and it was so thrilling, because I know that I’ve hit this big bone. I was brushing away and then I saw the tooth row. I had a big moment of excitement, because I knew that I had found part of the skull. … Anytime you find a skull in the fossil record is really, really rare, and so this was exciting for that reason.”

They were unable to continue with the field work due to the need to cover up the site before the weather turned colder. It is therefore not clear how many pieces of this Prognathodon are still in the ground.

“We know that there was a little bit of material underneath when we were digging up and we didn’t have time to excavate it,” she said. “So we buried it really well. It should be safe until next year, when we can go back and continue to dig.”

The fossil pieces that were found this year are now in the RSM preparation laboratory in Regina, where skilled specialists are undertaking a delicate task.

“The bone was very close to the surface and so it’s very fragile,” she said. “It falls apart really easily and we have to be very careful when preparing it. So the preparation is taking a little while. That will probably take another couple of months and then again we hope to go out next year to find more of the specimen. Eventually we hope to be able to put it on display at the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Regina.”

The Prognathodon was a large member of the Mosasaur family of aquatic reptiles. It lived about 74 million years ago during the Cretaceous period. It is often referred to as the T. rex of the sea, because it was a top predator in the Western Interior Seaway, which was a shallow continental sea that extended from the Gulf of Mexico through Saskatchewan to the Arctic Ocean.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.