Study investigates ways to make pronghorn crossing of highways safer

Posted on 9 March 2022 by Matthew Liebenberg

Road infrastructure on the prairie has a significant impact on the movement and migration of the pronghorn, North America’s fastest land animal.

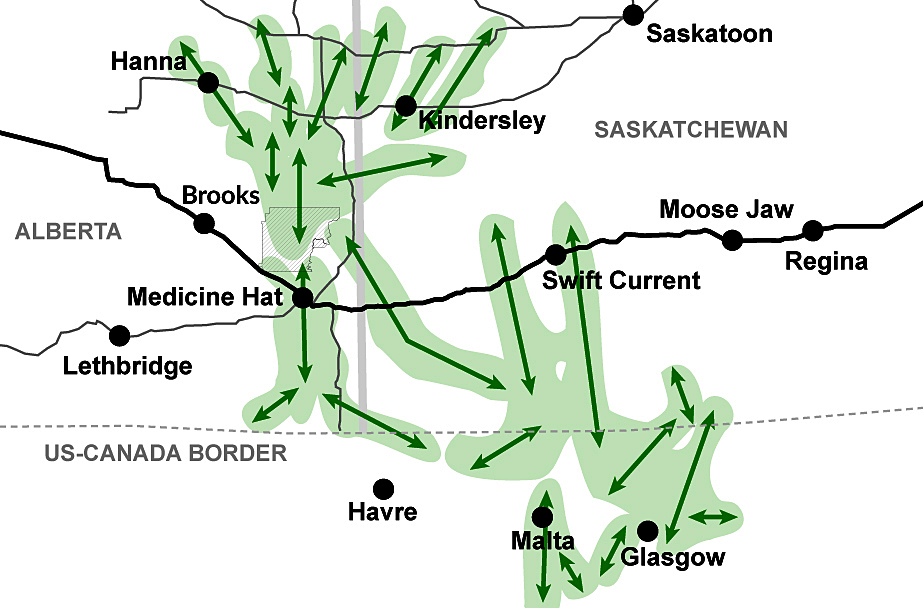

A multidisciplinary research project with a citizen science component has identified several areas along the Trans-Canada Highway between Brooks in southeast Alberta and Swift Current in southwest Saskatchewan where road improvements can support pronghorn conservation.

Pronghorn Xing is a collaborative project between the Miistakis Institute at Mount Royal University, Alberta Conservation Association and National Wildlife Federation.

Project guidance was provided by a working team that included representatives from the Nature Conservancy of Canada, Canadian Wildlife Federation, Alberta Transportation, Alberta Environment and Park, Saskatchewan Government Insurance, Saskatchewan Environment, and Saskatchewan Highways and Infrastructure.

Tracy Lee, a senior project manager at the Miistakis Institute, was the lead author of the report Pronghorn Xing: Improving pronghorn migration through road improvements, which was published in September 2021. This report details the results of the research work done from 2017 to 2020 and also indicates the next steps.

“The original motivation was the concern about pronghorn migration and movement across the Trans-Canada Highway,” she said. “Traffic volumes tend to increase over time and we were concerned about pronghorn’s ability to successfully cross that road into the future.”

Paul Jones, a senior biologist at the Alberta Conservation Association, said research data highlight the impact of the Trans-Canada Highway on pronghorn movements. Researchers started a GPS collar program in Alberta in 2003 to track animal movement and around 2007 some collars were fitted to animals in Saskatchewan and Montana.

“What we noted, especially the Alberta data, is when animals were making their migrations, they were really getting hung up on Highway 1, especially to the east of Medicine Hat,” he noted. “So they spent three days moving back and forth parallel to the fence on the south side of the highway before they actually got across the highway and then started moving north. There are really pinch points in the movement and migration of pronghorn in Alberta and we also see it based on modelling efforts that Dr. Andrew Jakes did for his PhD work in Saskatchewan as well.”

Pronghorn is the second fastest land mammal in the world and they can reach speeds of almost 100 km/h. They can use their speed effectively to cross a road without fences, but the Trans-Canada Highway presents a significant barrier to them.

“Roads really stress animals out, because they’re hard for animals to cross, especially if they’re fenced on both sides, like Highway 1 is,” he said. “We’ve got a fence on one side and four lanes of traffic with a wide meridian in-between. Then another fence to get across, and then even on the north side of the highway a railway and a fence on the other side of that to cross.”

The Pronghorn Xing project used information from three data sources to identify locations where pronghorns are likely to cross the Trans-Canada Highway and six secondary roads in the study area between Brooks and Swift Current.

A pronghorn connectivity model, which was developed by wildlife biologist Dr. Andrew Jakes, provided data about the spring and fall migration patterns of these animals in the study area. Information about animal vehicle collisions was used as another data source.

A citizen science program called Pronghorn Xing was the third data source. These citizen scientists were volunteers who used a freely available smartphone application to report any pronghorn sightings during road trips in the study area.

A total of 934 pronghorn observations were reported through the use of this smartphone application, of which 419 were along the Trans-Canada Highway and 515 were on secondary roads. Lee felt the citizen science program was an important component of the research project, because it helped to address data gaps and to engage the public meaningfully in conservation.

“It generated a data set that shed really important light on where pronghorns are crossing,” she noted. “So it supplied us with an information need that we had. … And equally important, this project helped us engage people and understanding the issue better.”

She added that the design of appropriate road infrastructure for safer pronghorn crossings will require investment of public dollars, and the citizen science component of the project helped to create a better public understanding of the need for such conservation efforts.

“So we need people who understand the issue and are supportive of that investment, building what they call the social capital or awareness about pronghorn conservation,” she said. “I believe that this project was a vehicle for us to do that. This project helped us engage people and understanding the issue better.”

The project team used the information from the three data sources to identify 16 potential pronghorn road mitigation sites along the Trans-Canada Highway. A set of criteria was then used to evaluate and score the suitability of each site. This process resulted in the identification of four priority sites where road mitigation measures will be most effective to help pronghorn cross the highway safely.

The four priority locations are an area of the highway near Canadian Forces Base Suffield between Brooks and Medicine Hat, a stretch of highway just east of Medicine Hat, and two areas along the Trans-Canada Highway in Saskatchewan. One area is located west of Maple Creek and the other area is a section of highway between Tompkins and Gull Lake.

The next phase of the project will focus on identifying specific sites within the four priority locations that will be most suitable for mitigation infrastructure to help pronghorn cross the Trans-Canada Highway.

“We have found from our experience that once you identified kind of roughly an area, then we go on the ground with the transportation professionals to look at the landscape and understand the land ownership and the landscape characteristics to see where the best location is for infrastructure,” she said.

Fencing can inhibit pronghorn movement and the intention is to develop a better understanding of how fencing influences movement in the study area. Land use intent must be considered to ensure that mitigation infrastructure for pronghorn is not located in an area where future development and human activity might increase. Land ownership must also be reviewed, because mitigation infrastructure will require land with conservation easement or ownership on both sides of the highway.

“Our next steps through the next two years are to work through those really important challenges,”Lee said. “That will help us identify where the best sites specifically are for infrastructure in those four areas that we’ve identified.”

Suitable road mitigation measures include wildlife overpasses or underpasses used in association with appropriate fencing and signage. Research data appear to indicate that pronghorn prefer overpasses, which is more expense to construct.

“A lot of that work is coming out of Wyoming, where they’ve done some comparisons in terms of the use of overpasses versus underpasses by pronghorn,” Jones said. “They found overpasses were used significantly more. It makes sense, because pronghorn evolved on the prairies of North America and their major defence against predators is detection by eyesight. They have to be able to see the landscape. They have fantastic eyes. They can see movement a mile or two away. So when you think about it, when you have an underpass, the visualization on the other side is very limited.”

Although overpasses will be the obvious solution if cost was not a factor, the study will consider the potential of other options as mitigation infrastructure for pronghorn.

“We’ll also explore some potential other opportunities where maybe it’s an underpass that’s wider than your typical underpass and cheaper than an overpass,” he said. “So a wider span bridge underpass to create that open habitat that pronghorn can see and maybe they’ll be able to get through. Sometimes it’s as simple as creating awareness with vehicles on the highway to let people know this is a key time when pronghorn may be crossing the highway.”

More information is still required with regard to the suitability of fencing for pronghorn crossing in the priority areas along the Trans-Canada Highway.

“Pronghorn will not jump a fence most of the time like a deer will,” he said. “Over 99 per cent of all fence crossings done by pronghorn are by crawling under that bottom wire. If the bottom wire isn’t high enough, that fence now becomes a barrier and then there are other indirect consequences of fences. If the wire is a little bit low and they crawl under it, it strips all the hair off their back and then that can lead to injuries and infection.”

For Jones the relevance of this study and the need for appropriate mitigation infrastructure along highways are related to the importance of pronghorn as an endemic North American species.

“They’re only found here in North America, and they’re actually not even related to the antelope of Africa,” he said. “Their closest relative genetically is actually the giraffe. … And then our pronghorn populations, especially here at the northern periphery of their range, are really susceptible to winter conditions. If they’re not able to move during the winter, that’s when we get those mass die-offs. So in essence we need to be able to keep pronghorn moving on the landscape if we want to keep them actually on the landscape. If we can reduce the stress and the time it takes to get across major highways, then I think we’re further ahead in terms of keeping pronghorn on the landscape.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.